|

Metaphor(m): Engaging a Theory of Central Trope in Art

Mark Staff Brandl |

|

|

Prelude

Tropi, Agon et Quo Vadam

Theories are

constructed objects. … They assembled a theory.

—George Lakoff (The Conceptual Metaphor Home Page)

(1)

A Personal Beginning

In

the early 1980s, the artworld was in an uproar. It was increasingly clear

that Modernism had, surprisingly, indeed been a “period,” not the ultimate

state of culture, and furthermore that it was slowly coming to a close.

Postmodernism seemed a little insipid, even unappealing at first as diverse

anti- or retro-styles vied for the pole position. French literary theory of

a Deconstructivist bent slowly became hegemonic, a situation still now in

place. Yet, for most artists and authors, Post-Modernism (still capitalized

and hyphenated at that time) seemed an opportunity to seek new theoretical

inspiration, to free oneself of the previously prevailing Formalism, also

termed the New Criticism in literature, while hopefully also offering a way

to avoid the trap of what threatened to be a cynical mise en abyme of

sophistry under the first influences of Poststructuralism. In heated

discussions in New York and elsewhere, artists sought out new

interpretations of the inevitably intertwined dialectic of form and content.

Art was clearly not all about form, it was plain to see that creators had

something to say, to discover. Equally, art was not all about the inability

to say anything,

-------------------------------

(1)

George Lakoff, et al., Conceptual

Metaphor Home Page (University of California at Berkeley

website, http://cogsci.berkeley.edu/lakoff/), page: http://cogsci.berkeley.edu/lakoff/metaphors/

Theories_Are_Constructed_Objects.html.

|

|

Prelude

iii

about illustrating the

unreliability of form as sole content. There was a widespread recognition

that, indeed, form was a tool for discovery and yet also the discovery

itself. Through that fissure, the great beast, long considered dead,

re-arose in a new and splendid form: ludic trope. At first the source of

inspiration for many artists, including myself, was Jacques Derrida and the

Yale Deconstructivists such as Paul de Man.

Jacques

Derrida was a French literary philosopher and the founder of what is called

Deconstruction. He argues that much of philosophy rests on arbitrary

dichotomous categories, sees language as writing, uses the metaphor of

"text" for all experience, and suggests that there is no possibility of

intentional meaning. Deconstruction can and has been disparaged as

nihilistic, solipsistic, and a-political, but has also contributed greatly

to the contemporary critical analysis of art and society, attacking

seemingly fixed notions of gender, race, and privilege. I found

Derrida's notions most interestingly presented in Writing and Difference,(2)

and Margins of Philosophy,(3) although Of Grammatology(4)

is his most popular book. Many of the theorists affiliated with Yale

University in the late 1970s, including Paul de Man, Geoffrey Hartman, J.

Hillis Miller, and Harold Bloom, are especially influential in literary

criticism and, influenced by Derrida, are called the "Yale Deconstructivists."

One of De Man's key texts in my opinion is The Resistance to Theory.(5)

Theory

in this vein remains the most powerful force in literature and art

departments in universities around the US and indeed the western world. As a

rather trendy art gallery owner once commented to me in 2003, “Aren't ALL

contemporary artists Derridaian and poststructuralist now?”(5) While this

may appear to be true, many of the artists, authors and students who

identify themselves with poststructuralist thought do not fully understand

it, not truly applying their own preferred theory. They are generally citing

it as an influence for fashionable reasons, verbally espousing many of its

tenets, such as the impossibility of fixed

-------------------------------

(2)

Jacques Derrida, Writing and Difference, trans.

Alan Bass (London & New York: Routledge, 1978).

(3) Derrida, Margins of Philosophy, trans. Alan Bass (Chicago &

London: Chicago University Press, 1982).

(4) Derrida, Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

(Baltimore & London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976).

(5) Paul de Man, The Resistance to Theory (Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press, 1986).

(6) Susanna Kulli, personal communication, St.Gallen, Switzerland, 2003.

|

|

Prelude

iv

interpretation, the

death of the author, and others. Denis Dutton describes this situation in

his article of 1992, “Delusions of Postmodernism” from the journal

Literature and Aesthetics:

That contemporary artists are as eager as

ever for attention as unique individuals is demonstrated by the fact that

they tend to treat their work as an expression of individual subjectivity

in discussion and documentation. That the privileged position of the

author/artist is not entirely dead in the minds of artists is also

indicated by the unceasing tendency of artists everywhere—including those

who style themselves “postmodern”—angrily to dispute hostile critical

interpretations of their work which “fail to comprehend” their intentions,

which “miss the point” of their work. For many artists, complete freedom

of interpretation is fine as a general philosophical theory applied to

other people’s work, but not to their own. (7)

What

began as a situation promising a possibility for more free artistic play,

has unfortunately now become the dominant master of the academy. Renowned

art historian, psychologist and art critic Donald Kuspit has asserted in an

email that, “In the artworld, followers of Derrida are not against hegemony;

they now possess almost complete hegemony.” (8)

It

was in this context that my study of literary theory arose — perhaps a bit

defensively, yet also out of enthusiasm. In fact, it was more of a return to

previous pursuits than a new interest. Throughout my university studies and

in my free time I have been actively involved in aesthetics, the analytical

philosophy of art. This passion operates in concert with my ardor for and

interaction with the possibilities of an “extended” interpretation of the

(supposedly dead) medium of painting, of installation art, of comics as an

artform, and of display sign-painting. Indeed, I even began my doctoral

studies in the department of English Language and Literature (called in

German 'Anglistik') in order to concentrate on the linguistic options of my

endeavor. Later, after I had completed the learning of Latin as a portion of

my studies, another opportunity arose as the University of Zurich finally

had a scholar of modern and contemporary art as a professor, Dr Philip

Urpsrung, whom I met personally when we both were speakers at the convention

of art historians in the US in Boston, The 2006 College Art

-------------------------------

(7) Denis

Dutton, "Delusions of Postmodernism,"

Literature and Aesthetics 2 (1992): 23-35.

(8) Donald Kuspit, Email

to author, Dec. 2004.

|

|

Prelude

v

Association conference.

Almost simultaneously I became acquainted with Dr Andreas Langlotz of the

University of Basel, an expert in cognitive linguistics. These events led me

to change to art history, leave my original, more orthodox literature

advisor, and begin afresh with the stimulating new influences of Ursprung

and Langlotz. Professor Ursprung understood not only my focus, but

encouraged me to reach for a whole new form of dissertation, suggesting not

only that I investigate other artists' works, both historical and

contemporary, but that I also include my own art in it as an integral

component, the performative presentation of the creation of these

dissertation works and an attempt to analyze them with the tool of my

theory. I was thrilled and yet presented with a whole new range of

challenges, which I hope I master.

At

first my theoretical research consisted of working my way through key books

and articles by and about the most influential poststructuralist

practitioners of literary theory and of what has come to be called

"critical" theory, the expansion of literary critical theories into the

discussions of socio-political questions. Simultaneously, I intensified my

already existing involvement with contemporary analytic aesthetics. In both

fields, I was seeking points of conjecture which I felt illuminated my

understanding of art in unexpected ways, yet also rang true to my experience

as an active artist, art critic, art historian and appreciator of

contemporary art by others. I was inspired by concepts from many thinkers,

as I describe in the next chapter, yet not the entirety of anyone's system.

I have thus sought to incorporate ideas I find enriching from a variety of

sources into my own theoretical construction. I now realize that an ulterior

motive was also to be able to theorize myself out of the constraints of

theory, fighting fire with fire as is often my wont. I sought to discover

philosophers offering pertinent , contemporary analysis which, however, also

acknowledged agency, that creators were responsible makers of meaning and

not mere symptoms of societal flaws. In truth, I heartily hoped for

theorists who would go even farther, searching for ones who suggested

intelligent means of resistance to an at that time ever-increasing dominance

by the radical right of politics and mass media; likewise, seeking

methodologies which could serve as insurrection against the even then

quickly hardening academic stifling of art in consensus and market

sophistry. Books important to me then included Hans-Georg Gadamer's

Truth and

|

|

Prelude

vi

Method, (9) Bakhtin, Essays

and Dialogues on His Work edited by Gary Saul Morson, (10) Arthur C.

Danto's The Philosophical Disenfranchisement of Art, (11), John

Lechte's Julia Kristeva, (12) Cornel West's Prophetic Reflections:

Notes on Race and Power in America, (13) and R. A. Sharpe's

Contemporary Aesthetics: A Philosophical Analysis. (14)

I

learned from all these and more. However, most crucially, I found the

greatest revelation in the cognitive linguistic approach of George Lakoff

and others and in the antithetical revisionist theory of Harold Bloom.

Combined, they accorded genuinely with my experience of art while also

electrifying me with new possibilities for understanding art, its production

and its producers. Cognitive linguistic theory was first widely introduced

in Lakoff and Mark Johnson's Metaphors We Live By (15) and

Lakoff and Mark Turner's More than Cool Reason: A Field Guide to Poetic

Metaphor. (16) Bloom presented his theory initially in a trilogy

of books beginning with The Anxiety of Influence.

(17)

Trope and Struggle

Although also first appearing in the late 80s, cognitive

metaphor and the embodied mind concept took until the turn of the millennium

to begin affecting the practice and understanding of creators and scholars.

Cognitive linguistics, especially the subdivision of it

-------------------------------

(9) Hans-Georg

Gadamer, Truth and Method, revised trans. Joel Weinsheimer and

Donald G. Marshall (New York: Seabury Press, 1989).

(10) Gary Saul Morson, ed., Bakhtin, Essays and Dialogues on His Work

(Chicago:

The University of Chicago Press, 1986).

(11) Arthur C. Danto, The Philosophical Disenfranchisement of Art

(New York: Columbia

University Press, 1986).

(12) John Lechte, Julia Kristeva. (London: Routledge, 1990).

(13) Cornel West, Prophetic Reflections: Notes on Race and Power in

America. (Monroe, Maine:

Common Courage Press, 1993).

(14) R. A. Sharpe, Contemporary Aesthetics: A Philosophical Analysis.

(New York:

St. Martin’s Press, 1983).

(15) George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By (Chicago:

The University of Chicago

Press, 1980; paperback, 1981).

(16) Lakoff and Mark Turner, More than Cool Reason: A Field Guide to

Poetic Metaphor (Chicago: The

University of Chicago Press, 1989).

(17) Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence (Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 1973).

|

|

Prelude vii

which I will use the most called cognitive

metaphor, is largely based on the ground-breaking work of George Lakoff and

his two collaborators, Mark Turner and Mark Johnson. Lakoff, who began as a

student of Noam Chomsky, initiated research which led to the creation of an

important interdisciplinary study of metaphor, now generally called

cognitive linguistics. Theorists involved in this approach advance the

hypotheses that metaphor is the foundation of all thought, that linguistic

elements are conceptually processed and that language is chiefly determined

by bodily and environmental experiences.

The desire for an

imminent fundamental change linked to a new understanding of trope is indeed

in the air, not only for me; ever more frequently, artists and authors have

begun to refer to metaphor and cognitive metaphor theory. For example, Frank

Davey, a Canadian poet with an involvement in theory, states the following

in an interview with Héliane Ventura in the journal Sources:

Lakoff

and Johnson suggest that many of our habitual metaphors are connected to

our culture’s ideological investments. ... To some extent their work

appears to be related to various projects of Deconstruction, in that they

raise to consciousness the hidden assumptions of banally figurative

language. Political and economic metaphors, they write, “can hide aspects

of reality,” “they constrain our lives,” they “can lead to human

degradation.” But they also argue that ordinary language is necessarily

metaphoric, that cultures need the conceptual frames of metaphor to

provide perspectives and coherence. And I recall that as well they examine

metaphors around women—women as food (“a real dish”) or as fire (“hot

babes,” “hot stuff,” “kiss of fire,” “torrid romance” etc). It’s this ...

kind of metaphor that I play with in Back to the War in poems such

as “The Complaint,” or “Sweets,” or “The Fortune Teller.” ... The ‘link’

that metaphor requires isn’t foregrounded in [my poems] but is merely

latent until it is made by the reader.... (18)

Likewise, art critic Barry Schwabsky writes

of the influential New York painter Jonathan Lasker in Art in America

magazine:

-------------------------------

(18)

Héliane Ventura, "An Interview with Frank Davey,"

Sources, Revue

d'études anglophones

17 (August 2004):

74.

|

|

Prelude

viii

Jonathan Lasker once

told me he thought the Minimalists had been trying to make an art without

metaphor, and in fact had succeeded; but the point having been proved, he

continued, there’s no longer any urgent motivation to produce more

metaphor-free work. (19)

Cognitive linguistics and

Bloom's revisionism were a revelation to me. I found Bloom's notion of

agon to supplement Lakoffian conceptions splendidly. Bloom sees the

primal activity of the creative life as one of struggling with and

overcoming one's influences by revisionistically, willfully and yet

imaginatively misunderstanding them. In cognitive linguistics and agonistic

revisionism, I discovered theories which read true to my experiences and

additionally offered openings to the world, criticizing the solipsism and

sophistry of much other current literary theory by, among other strengths,

subsuming their rivals' insights.

It can now be seen that the Late Modernist

attempt to undermine metaphor, as described by Schwabsky and Lasker above,

although necessary at that time, did not actually function as expected, but

was rather a negational, metaleptic trope in itself. Moreover, Davey

expresses a perception that there is a continuation between Derrida and

Lakoff , an opinion both controversial and, surprisingly, held by many. In

his eyes as a working poet, he finds aspects of Deconstruction and cognitive

metaphor to be akin, something that both factions would heartily rebuff. The

continuum containing both these theories is that of the free play of tropes.

The fascination and excitement of encountering and applying new conceptual

systems can lead to productive discoveries, both in the hands of creators

and of scholars, whatever their final political status becomes. Applying

novel theories can produce new discernments into literature and art

contemporary with a given philosophy, but also into aspects of the nature of

creativity across a broader time span.

Lakoffian

theory offers an, at this time, atypical model, in that it acknowledges

agency — that is, the individuals who make art experiences. This renders a

chance to investigate into and speculate on the nuts-and-bolts of creation.

The cognitive theory of metaphor is also unusual in that it is a theory more

concerned with concepts than with words alone, thus fostering application to

a wide range of art forms. An important facet of cognitive linguistic theory

is that metaphors are embodied, that is, that mental concepts are

constructed

-------------------------------

(19)

Barry Schwabsky,

"Jonathan Lasker - Brief Article," ArtForum

(September 2000). Cited from <http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0268/is_1_39/ai_65649484>

|

|

Prelude

ix

tropaically out of bodily experiences. These foundational perceptions can

furthermore lead to what he terms “image schemas,” which can then be used to

structure somewhat less physical events. This has potentially significant

implications for the poet, the painter, the novelist, the critic and the

scholar. It is indeed one of the main tools I have chosen to employ. In my

dissertation, Lakoffian theory will be applied to the competitive discovery

of trope within aspects of form in visual art.

Lakoff

believes that a proper appreciation for metaphor cuts through the perpetual

clash between the so-called “objective” view of trope (that it is purely

literary, almost decorative) and the so-called “subjective” view (that it

has no direct tie to experience). He promotes an alternative that stresses

the centrality of metaphor to our thinking processes, and thereby to our

language and other actions. Hence, I see cognitive metaphor theory similarly

offering an alternative to Formalism and Poststructuralism by subsuming them

both.

This study will use theory derived from cognitive linguistics

as a method of augmenting the range of poststructural thought and

revivifying appreciation of the formal discoveries of authors and artists.

Cognitive

metaphor theory proffers a mode of thinking which can be applied to the

analysis and creation of art, while accentuating the efforts of the makers

of these objects. After the object-only orientation of Formalism, after the

medium-only focus of deconstruction, this may lead to a feeling of

liberation, of agency. Nevertheless, this is a theory which brings with it a

new sense of the burden of the past. Whereas the Formalist Modernists felt

free from the past and the Deconstructivist Postmodernists are endlessly

tangled in an inescapable present, authors and artists as viewed through

cognitive metaphor theory are directly responsible for fashioning their own

tropes through the processes of extension, elaboration, composition and/or

questioning. This they accomplish in and through the formal parameters of

their work, with enough cultural coherence to be able to communicate, but

enough originality to be significant. Important tropes cannot merely be

selected from a list; they are discovered and built out of revisions of

cultural possibilities, in fact, fought for and won. Thus Harold Bloom's

theory of antithetical revisionism also contributes an important component

to this paper, as he writes:

But

again, why should someone crossing out of literary criticism address the

problematics of revisionism? What else has Western poetry been, since the

Greeks, must be the answer, at

|

|

Prelude

x

least in part. The origins and aims of poetry together constitute its

powers, and the powers of poetry, however they relate to or affect the

world, rise out of a loving conflict with previous poetry, rather than out

of conflict with the world. ... This particularly creative aspect of a

kind of primal anxiety is the tendency or process I have called "poetic

misprision" and have attempted to portray in a number of earlier books.

(20)

The heart of Bloom’s

theory of misprision is the concept of an indispensable, antithetical agon

of each poet. With poetry being the chief artistic discipline for Bloom, the

word poet may also be replaced here with artist, which is what

I will do. Revisionism is exalted to the central fact of artistic

creativity. Agon is Bloom’s term for the conflict arising from the

anxiety of influence. Each and every author must wrestle with his or her

precursors, the ones who inspired them to be writers in the first place. In

amendment of Bloom, though, this “loving conflict” also transpires with the

world, as it involves tropes of bodily experience as outlined in Lakoffian

theory. Creators seeking individual ways to convey their experiences within

their media, are necessarily forced to fence with comparable expressions of

similar experiences by their predecessors, therefore primarily with their

predecessors' tropes. Cognitive metaphor theory offers an important basis

for the study of art and literature, in particular their formation. Bloomian

agonistic misprision completes the portrayal of the process by which

creators arrive at the cognitive tropes so described.

The

theory of central trope which I will be developing within this dissertation

is postmodern, as dscribe. It is a model describing the construction by

authors and artists of distinctive central tropes in the tangible forms and

processes of their media. They achieve this by means of an agonistic

struggle with predecessors' tropes, doing so in order to uniquely articulate

personal perceptions and experiences.

Such tropes in

the hands of artists are both metaphoric and meta-formal, thus yielding the

punning term metaphor(m) in my title. This word describes and

embodies the core of the theory. For creators, artistic value is grounded in

form, the way a work is made and its technical aspects. Yet, turning

Formalism on its head, these attributes in themselves are significant only

due to their meta-properties as tools and modus operandi involving context,

tropaic content and cultural struggle.

-------------------------------

(20)

Harold Bloom, Agon:

Towards a Theory of Revisionism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982;

paperback, 1983), vii-ix.

|

|

Prelude

xi

This Dissertation

Cognitive metaphor theory will be put in the

service of art and art historical theory. In this dissertation, then, I will

develop a theory of how meaning is embodied in Modern and Postmodern

creativity. I view my hypothesis as the elucidation of a theoretical yet

concrete tool with which artists create. Based in part on linguistic theory,

metaphor(m) is a general theory of trope in art, which links content and

form with historical and critical cultural awareness. I will apply my theory

to visual art, especially to painting and installation art. The artists will

include the famous and the less well-known, historical and contemporary,

friends and foes, a smattering of all of these. I have been studying an

applying my theory to Charles Boetschi, Vincent van Gogh, Gerhard Richter,

Wesley Kimler, Stuart Davis, Jackson Pollock, Donald Judd, Leonard Bullock,

C Hill, Bill Viola, Robert Rauschenberg, Sigmar Polke, Lawrence Weiner,

Marcel Duchamp, George Brecht, Jack Kirby, Gene Colan, Jonathan Lasker,

Stephen Westfall, David Reed, Mark Francis, Mary Heilmann, Edith Altman,

Annette Messager, Joseph Beuys, Richard Long and many others. Who exactly

will turn up in my dissertation I cannot yet say for certain. Topics will

include specific and close analysis of artworks and media. While the theory

of central trope will be in dialogue with a number of theorists and creators

within my discussions, this dissertation is intended to be a work of

performed theory, not an exhaustive monograph on a single artist nor a

purely personal reflection. Rather, I will test my thesis through the study

of chosen subjects, while simultaneously working through the implications of

the theory on my own art as manifested in the planning and creation of a

painting-installation. In this way, I will probe metaphor theory’s bounds

and limitations, as well as its depth and utility in the study of creative

works. Thus my theorization will be embodied performatively, and what is the

creation of art, especially paintings, if not mentally guided bodily

experience.

I

will create this dissertation in the traditional form of a book, but with

the addition of an actual installation. If successful, both will manifest

the process of creation displaying, in open performance, the slow but steady

making and finding of a metaphor/m. However, much like Sigmund Freud’s

psychotherapy of himself, this may not be completely possible, opening my

dissertation to the rich possibility of partial failure. In either event, it

will be a thoroughly dialogical approach to production, uniting performance

and reflection in a manner perhaps best describable as a Deweyian

double-loop learning procedure or a Gadamerian hermeneutic circle of

understanding. Philosopher and education reformer John Dewey proposed that

|

|

Prelude

xii

learning was

more than the prevailing view described as error and then correction. He

believed learning to be a reiterating process of testing, learning,

correction and within re-testing modification of the underlying goal could

be altered, thus seeing it as two loops of correction. The philosopher of

hermeneutics, Hans-Georg Gadamer proposes that understanding is accomplished

by coming to a situation with preconceptions, testing these and then

necessarily altering ones judgment, resulting in ever repeating circles

through which one then

deepens the comprehension of any whole through knowledge of its parts

encountered in subjective yet open investigation.

Within

the writing and the concomitant creation of the art, I will perform a guided

tour of the installation, but one changing and allowing alternate paths,

perhaps enlisting the various aspects of such an exhibition as tropes and

forms: labels, comments, catalogue essay, sketches, plans, etc. Each chapter

of the dissertation, then, will embody the idea of the chapter through the

inclusion of analytical discourse, a painting, sketches and plans for the

installation, and a comic sequence featuring an investigation of how the

(meta-)discourse is being applied in the art works, in a plurogenic, braided

interlacing of registers, a methodology much inspired by Giuliana Bruno's

book Atlas of Emotion. (21)

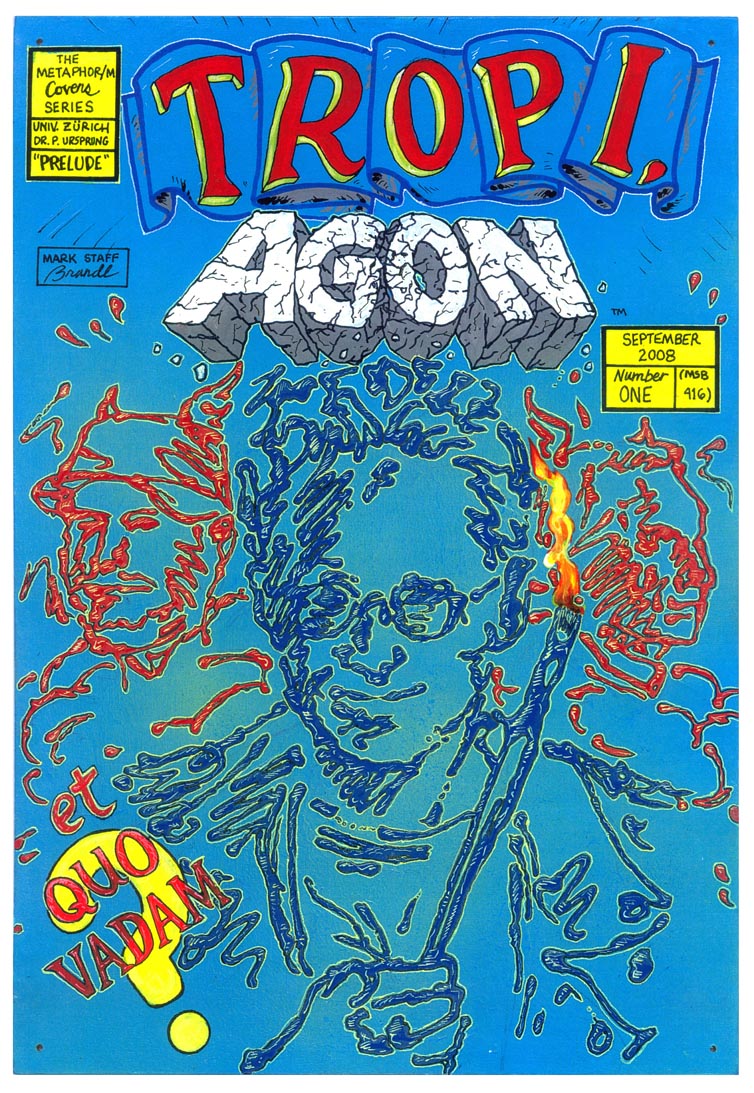

My

“painting installations,” which I term

Panels,

are wall and room-filling works wherein a group of large painted canvases

are surrounded by additional painting directly on the wall, thereby

transforming the space into huge, readable, sequential “pages” of a walk-in,

“comic book.” Second, there are the somewhat more detached paintings I term

Covers. These works are paintings in gouache, ink, acrylic and oil on

paper, wood panel, or canvas. They are recognizably based on the structure

of comic book covers, with title, bold lettering, price, date, numbering,

image and so on. Both types of artworks are frequently presented together as

one large installation.

Furthermore, important portions of the dissertation will be

posted on-line on an art “e-zine” as blogs, allowing for additional “viewer”

and reader discussion. My hypostatization of central trope will center on

testing it in the production of a Covers and Panels

painting-installation. Thus, I will be imagining, conceiving, and

bringing-into-vision the concept of central trope in art, as proposed in my

subtitle. Some Modernist critics are

-------------------------------

(21)

Giuliana Bruno, Atlas of Emotion: Journeys in Art,

Architecture, and Film (New York: New Left

Books, Verso, 2002; paperback, 2007).

|

|

Prelude xiii

dismissive of the possibility that various art forms and media might have

any similarities or effects upon one another. Most famously advocated by

Clement Greenberg, this form of Modernism asserts that each art must be

rendered “pure” by concentrating solely on what separated it from other

disciplines, especially demanding an anti-literary stance in visual art. By

contrast, my theory of central trope denies such separation, claiming an

underlying level of tropaic reasoning to be integral to literature, visual

art and creative works in other media, perhaps even postulating a necessary

postmodern impurity. Application of a conceptual theory of metaphor to art

history remains a relatively unexplored — but potentially very rich — area

of research.

In addition to the text, artworks, and

series of on‑line e‑zine articles (called blog posts) as mentioned, my

dissertation chapters will include sequential art (called comics), as well

as sketches for the installation and occasional groups of paintings

concerning tangential, associational thoughts. The image preceding this

"Prelude" was the first Cover painting. The page following is the

first of the meta-sequences in comic form. In the completed book, the

"Introduction" will either precede or follow this chapter, as of course

introductions are best written after the entire text has been completed, but

are presented at the beginning. The topic of the next chapter is "Wandering

and Surveying: Links and to Literary Theory and Contemporary Aesthetics." It

is a "placement" of the theory within the world of literary theory, as well

as a discussion of related approaches or influences from contemporary

analytical aesthetics.

|

|

|

|